NEWS

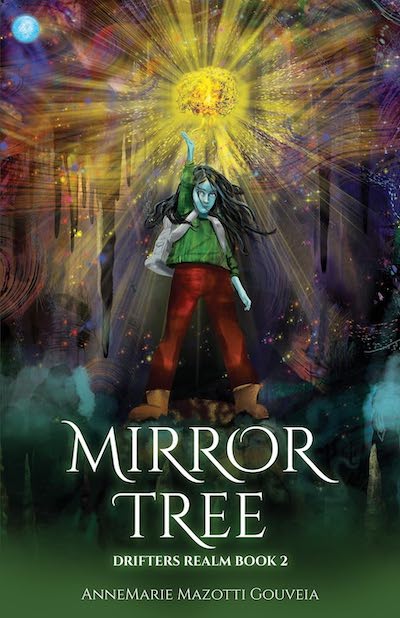

18 April 2024: Come meet AnneMarie Mazotti Gouveia for a book signing in celebration of Mirror Tree, the second book in her award-winning YA/fantasy series Drifters Realm! At the bookstore this Saturday, April 20, 2024 from 2-4 PM.

Drifters Realm

Mirror Tree

16 April 2024: Hot off the presses comes the thrilling finale to Glen Dahlgren's "Chronicles of Chaos" series, The Realm of Gods!

The Realm of Gods

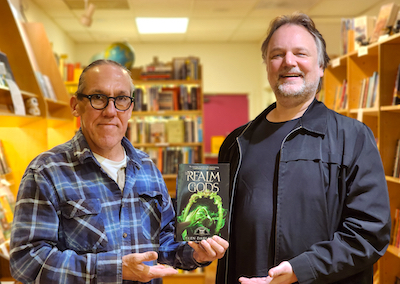

Rudy with author Glen Dahlgren

11 April 2024: Congratulations to Joanna Hill on the recent publication of her book on the well-being in all of us, The Well-Being In You: How 3 Simple Principles Can Help You Tune into Your Innate Psychological Health and Thrive!

The Well-Being In You

Joanna Hill

9 April 2024: Since we opened in 2020 we've enjoyed watching Deven Greene's Erica Rosen MD Trilogy grow on the shelves of Reasonable Books, and we're pleased now to share her latest novel with you, Ties That Kill: A Mid-Life Crisis Thriller!

Ties That Kill: A Mid-Life Crisis Thriller

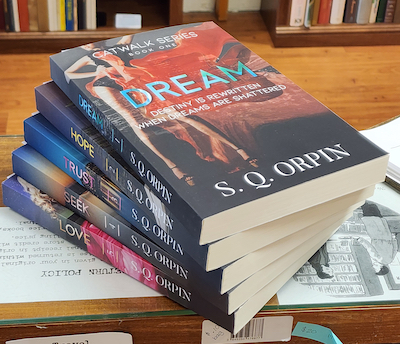

3 April 2024: Native Canadian and Lafayette resident Suzy Quenneville-Orpin joins us with two book series for fans of Women's Fiction... and cooking! The first is the five-part Women's Fiction Series Catwalk, and the second accompanies it with five cookbooks in the Cookbook Companions series.

S.Q. Orpin

The Catwalk Series

The Catwalk Series Cookbook Companions

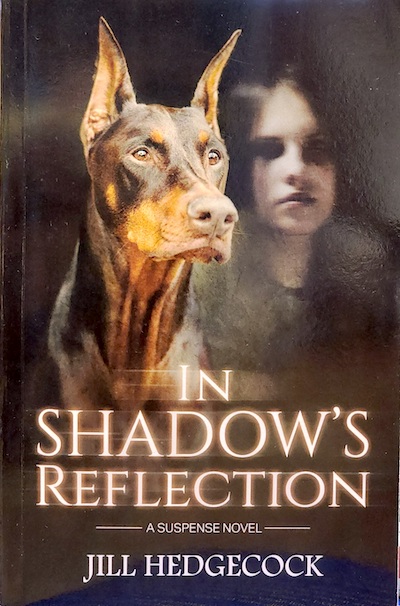

26 March 2024: We're looking forward to our event this Saturday at 3:30PM with Jill Hedgecock and Kevin Fisher-Paulson! Some wet weather is looking likely, which makes RSVPing especially important. Please call us at 925-385-3026.

We are also very excited to tell you about a few new books by local authors, as well! The first is The Mirror Tree by AnneMarie Mazotti Gouveia, the second book in the Drifters Realm series.

The Mirror Tree: Drifters Realm Book 2

In The Mirror Tree, Book Two of the Drifters Realm fantasy adventure series, twelve-year-old triplets Ori, Roe, and Tora, along with their older brother Theo, must trust their unpredictable magic and each other. Together, they attempt to stop the Guardians, whose supernatural powers are controlled by their uncle, First City Leader Zane. He is determined to steal Ori’s Sorcerer Obligation and impose his oppressive rule beyond their realm. As peril intensifies, the lines between right and wrong blur and the siblings fight to stay one step ahead of danger. They traverse through forests, deserts, caves, and swamps with the assistance of Ori and Roe’s ancient rings, their friends, and the outcast teenagers known as the Menace.

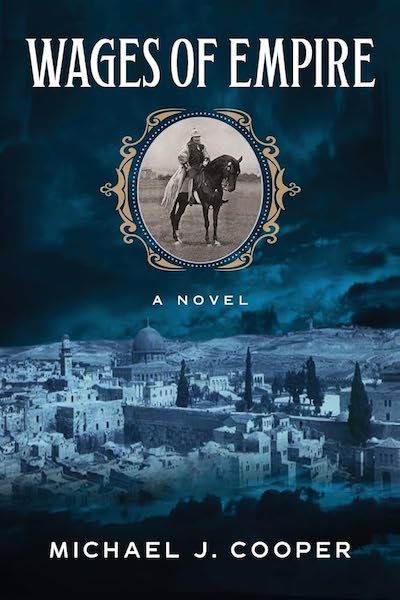

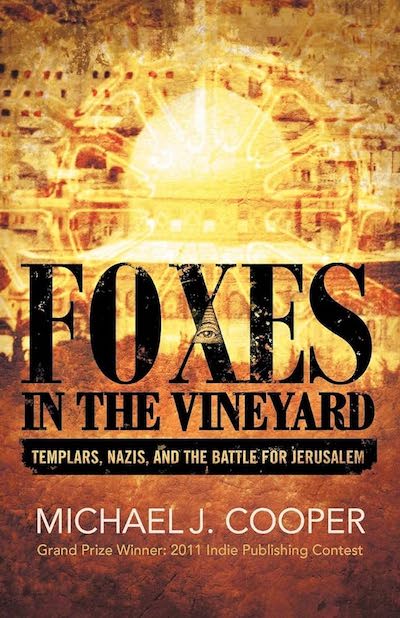

Local author Michael J. Cooper brings us two novels of historical fiction set in and around Jerusalem both before and after 1948, Wages of Empire and Foxes in the Vineyard.

Wages of Empire

In the summer of 1914, sixteen-year-old Evan Sinclair leaves home to join the Great War for Civilization. Little does he know that, despite the war raging in Europe, the true source of conflict will emerge in Ottoman Palestine, since it's from Jerusalem where the German Kaiser dreams to rule as Holy Roman Emperor. Filled with such historical figures as Gertrude Bell, T.E. Lawrence, Winston Churchill, Faisal bin Hussein and Chaim Weizmann, Wages of Empire follows Evan through the killing fields of the Western Front where he will help turn the tide of a war that is just beginning, and become part of a story that never ends.

Foxes in the Vineyard

In April of 1948, Boston University history professor Evan Sinclair receives a telegram notifying him that his father, Professor Clive Robert Sinclair, has been reported missing from his post at the Palestine Archaeological Museum. Fearing for his father's well-being, Evan and Clive's longtime friend, Mervin Smythe, travel to Palestine on the eve of the first Arab-Israeli War. Evan finds his father and far more—a lost love, a son he never knew he had, and covert elements of the Third Reich positioned in Palestine before the end of World War II. Having infiltrated both Arab and Jewish populations, the Nazis seek to use counter-intelligence and terror to stoke the fires of hatred and fear between Arabs and Jews. The goal is to drive the British from Palestine and to seize Jerusalem as the capital of a reborn Third Reich with the legendary Knights Templar treasure as plunder and the Temple Mount as their fortress.

16 March 2024: As we look forward to our next in-store event with Jill Hedgecock and Kevin Fisher-Paulson (see below!), we are very pleased to welcome two new books by local authors Betsy Streeter and Grant Petersen! Betsy has been publishing her single-panel cartoons since the '90s, and along with collecting her Brainwaves work in four "best of" volumes, she has also teamed up with local bicycle guru Grant Petersen to illustrate his book of single sentence gems of wisdom from his experience in the world bicycles.

Best of Brainwaves Volume One:

The Fountain of Stuff

Brainwaves is a single-panel cartoon about the infinite absurdity of everyday life, whether it's the life of a person, a dog, a giraffe, a toaster, or a yam. Best of Brainwaves Volume One: The Fountain of Stuff covers the first 420 collected cartoons in the series, in the order they were drawn, and starting with the very first panels picked up by King Features in the 1990s. Streeter makes fun of technology, consumer culture, pets, bugs, working, cars, space, and just about anything else.

Bicycle Sentences

Bicycle Sentences is 177 sentences about bicycles and riding, stuff you may know or might not know, may believe or might not. It's not a Rule Book, not a Holy Book. I believe them all, they’re all true for me/Grant, and some may be true for you or worth experimenting with, and who knows what else?

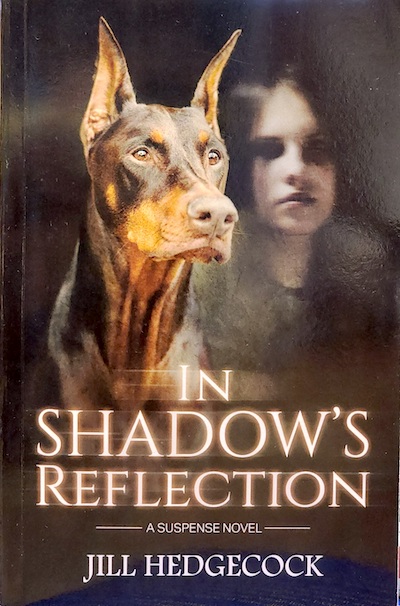

12 March 2024: You will want to mark your calendars for our next great in-store event with Jill Hedgecock and SF Chronicle columnist Kevin Fisher-Paulson, on Saturday March 30th at 3:30 PM! This event will celebrate Jill's latest book In Shadow's Reflection, as well as Kevin's latest, Secrets of the Blue Bungalow.

In Shadow's Reflection

Sarah and her Doberman Shadow are back again in this intense series about mystery, discovery, and a young woman’s incredible journey into her past so masterfully captured by author Jill Hedgecock. Sarah’s innocent questions about her family open up an unexpected Pandora’s box. The bond between a girl and her Doberman is so beautifully on full display while the story simultaneously engrosses the reader in a world where the past may be darker, but the future brighter, than you would have guessed. Read this book and take this journey, you won’t forget it. — John Walter

Kevin Fisher-Paulson

For eight years, thousands of readers across San Francisco and beyond have laughed, cried, and felt inspired by the true, tender, and hilariously honest tales of a gay-parented, mixed-race, superheroic family growing up together in a Bedlam Blue Bungalow... located somewhere in the Outer, Outer, Outer, Outer Excelsior neighborhood. Told every Wednesday by SF Chronicle columnist Kevin Fisher-Paulson, 65 of these evocative stories were first collected in a 2019 book entitled How We Keep Spinning...! the journey of a family in stories. Four years later Secrets of the Blue Bungalow: More True Tales of Family Life in the Outer, Outer, Outer, Outer Excelsior shares 75 more true tales of family life at the very edge of San Francisco, as experienced by Kevin, Brian, Aidan, Zane and their faithful rescue dogs.

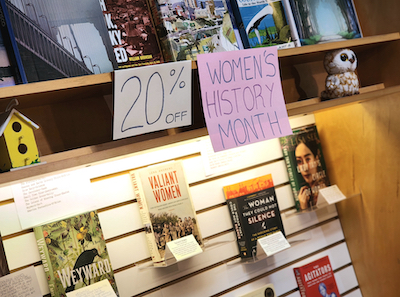

2 March 2024: March is Women's History Month, and we're featuring a selection of books for the occasion at 20% off throughout the month! You can see these books in the shop on shelf 79 (this is the built-in display shelf with the stuffed owl and tiny birdhouse). You can also find them by searching on our website with this link. We're also mirroring the list on Bookshop.org, and in audio format at Libro.fm! (Different promotions apply at these online locations.)

Shelf 79

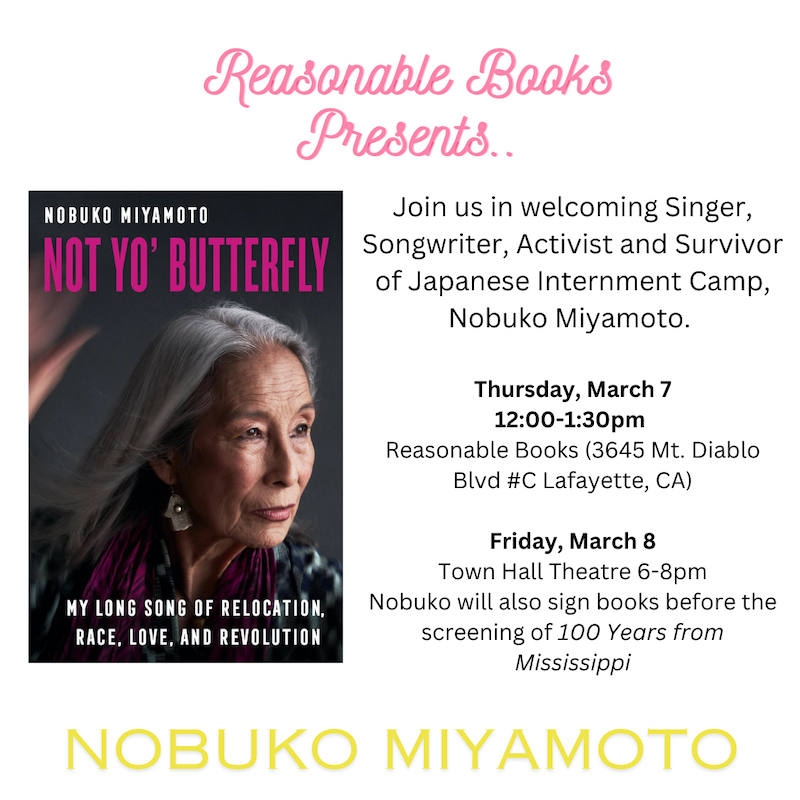

28 February 2024: Mark your calendars for our next event, a weekday author visit from Nobuko Miyamoto, who will be discussing her book, "Not Yo' Butterfly" here at noon on Thursday, March 7th! RSVPs may be sent to books@reasonable.online.

As people across the country and around the world became antsy while enduring iterations of the pandemic lockdown, Nobuko Miyamoto dug deep into her creative well to find the silver lining—composing and releasing the album 120,000 Stories in December 2020, and writing and delivering her debut memoir, Not Yo’ Butterfly: My Long Story of Relocation, Race, Love, and Revolution, in June 2021. As a child of relocation who was incarcerated in a Japanese internment camp during World War II, a woman who was forced into single parenthood in her early 30s when the father of her biracial son was killed and a lifelong activist, the now-83-year-old Miyamoto has endured things much more difficult than sheltering-in-place. And, as we now readjust to life as we knew it during pre-pandemic times, Miyamoto is excited to share her work with the world. - Sharon K. Sobotta, East Bay Express

Nobuko Miyamoto at Reasonable Books

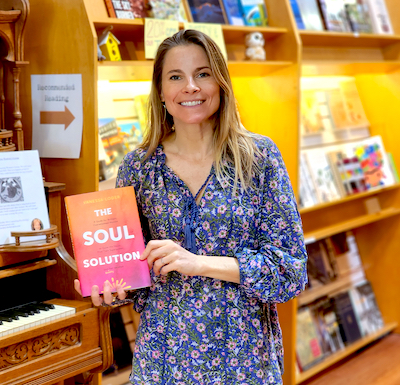

24 February 2024: Women’s leadership expert, writer, speaker and energetic sparkplug Vanessa Loder joins our local authors with The Soul Solution, a nonstrategic, nonlinear—but entirely effective—guide to help you reclaim your feminine, intuitive soul power to fulfill your most meaningful and satisfying desires. Welcome, Vanessa!

• The Whispers of Your Soul—the three key steps for tuning out the noise and accessing authenticity

• Your Energetic Bread Crumbs—how the universe signals to you when you’re on the right path

• Discover Your Superpower—why you’ve been ignoring your most valuable gifts, and how to reclaim them

• From Tunnel Vision to Visionary—ways to break out of the “shame cycle” of patriarchal culture and own your destiny

• Quieting the Inner Critic—how to retrain your inner voices to encourage and support you

• The Upward Spiral—using the SAT method (Surrender, Allow, Trust) to get more of what you want with ease.

The Soul Solution

Vanessa Loder

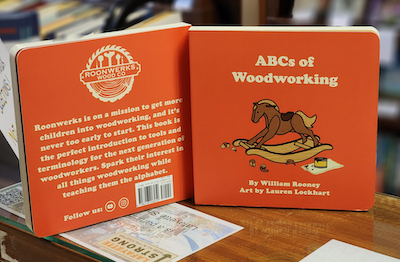

21 February 2024: Welcome to William Rooney and his children's board book for future woodworkers, ABCs of Woodworking!

ABCs of Woodworking

Remember, "O" is for Orbital Sander!

6 February 2024: We are starting a new program for book clubs! Since we opened in 2020 we've had the pleasure of getting to know many avid readers from the Lamorinda area, and we've noticed that many of you belong to book clubs. We'd love to learn more about what your club's interests, and how we can help you get the most out of your book reading.

Calling All Book Clubs!

To that end, we're inviting local book clubs to register with us and receive discounts of new copies of the books your clubs are choosing to read. To register, please visit or email us, letting us know the name of your club and the contact information for a club member to whom we can reach out for book club related news.

When your club is registered, you can then let us know what book you have chosen to read for the current month, with a discount on this book of 20% for your club members! This way, we can make sure we have some copies of your book in the store, and of course, we're also happy to order specific quantities of books for your club members to purchase! Please let us know if you have any questions about this program, either in person or by sending us a note at books@reasonable.online.

2 February 2024: The East Bay's own photographer and poet Scott Slocum has recently published his first book, The Trails We Travel: Moments in Amazement, a collection of poems accompanied by poignant images from the scenic hillsides of Northern California. This is a book for literary hikers and other lovers of the natural beauty of the East Bay and beyond!

The Trails We Travel

Scott Slocum

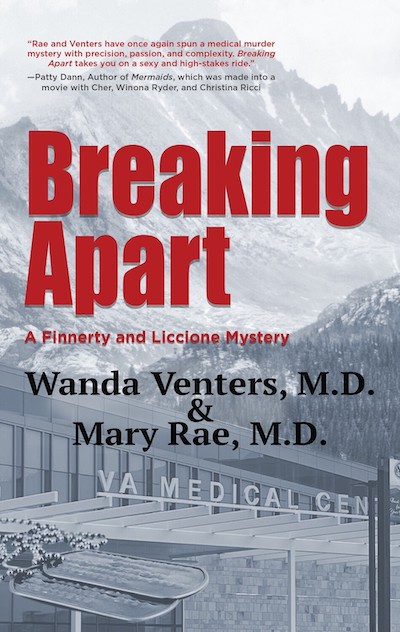

20 January 2024: We are pleased to congratulate Wanda Venters and Mary Rae on the release of their second Finnerty and Liccione Medical Mystery, Breaking Apart!

Dr. Marnie Liccione and Dr. Louise Finnerty team up again to investigate the violent death of a young veteran at a Colorado VA Behavioral Health clinic. Was it suicide or murder? Questions from Josh’s widow, who feels that her world is breaking apart after his death, convince Marnie and Louise there’s more to the story. In their search for answers, they uncover a prescription drug diversion scheme masterminded by those who may be also involved in the illegal sale of krokodil, a deadly and disfiguring opiate. As they move closer to the truth of the circumstances surrounding Josh’s death, sinister forces will threaten their lives. Will they find the answers they need to give his widow solace?

Breaking Apart

13 January 2024: Congratulations to local author Bruce Lewis on the release of his Angel of Mercy series! These mysteries feature Jim Briggs, a veterinary surgeon who volunteers his time helping the unhoused in a most unusual way.

Veterinary surgeon Jim Briggs has helped ten Chicago homeless people commit suicide. To the residents of the Lazy Acres homeless community, Briggs is an angel of mercy. He cares for their dogs for free and provides those in need with a pain-free exit from the city's harsh winters and brutal life on the street.

Angel of Mercy

Human Strays

Family Curse

The Red Flock

11 January 2024: 2024 is starting with some exciting news from us here at Reasonable Books, where we are pleased to introduce Linda Grana, the newest member of your Reasonable Books staff!

Many of you will know Linda from her tenure as manager at Lafayette Bookstore. You may also know her from Diesel Books (now East Bay Booksellers), or from her online book reviews and reading groups. Linda’s sage advice since we opened in 2020 can be felt throughout the store. Betty and Linda have some exciting ideas to work on in 2024, including resources and benefits for book clubs and their members, and they are kicking off the new year with their Top 10 lists of books from 2023. With that introduction, I will let Linda tell you more in her own words.

***

2023: Our Year In Books

2023 was definitely 'one for the books'! As we're just entering the new year, we've been reflecting back on the previous years' bookish gems.

Both Betty and I have painstakingly (so hard to choose!) compiled a list of our Top 10 favorites for 2023. I have made it a New Year’s tradition of mine for the past decade or so, and it's amazing to me that some years it seems difficult to come up with 10 titles that I feel are really worthy of the list; then others, like this past year, we both struggled to sort through our numerous favorites, narrowing it down to just the 10. In fact, Betty ended up having two "runners up", and I found myself having to include an "honorable mention"!

When we got together with our completed lists we were excited to find that we, not only had 3 books in common, but we had both chosen the same novel as our #1 Book Of the Year!

Rudy, Betty and I are anxious to have you drop by the store to see which title earned that number one spot for both of us. We're also excited to announce that we are offering a 20% discount on every book on our list through February 29th! Betty will be working hard to make sure that all have been ordered, and hopefully on hand when you come in.

So stop by when you can, and let's talk books! We'd love to hear about your personal favorites of 2023!

Linda

***

Linda will be working at the shop one day a week, and if you see her behind the counter please feel free free to say hello and welcome her aboard—and of course, to talk books! Thank you so much for your continued support of us here at Reasonable Books :)

Linda Grana

9 January 2024: Congratulations to local poet Valerie Sopher on her first chapbook, Day For Night!

Day For Night

Ask about the discount in celebration of Valerie's collection of poetry!

28 December 2023: Welcome to Laurie, Mary, Deborah and Johanna and their collection of poetry, Love's Meditation! In Love’s Meditation, four poets reveal their love for the world and their concerns for its future. Love’s Meditation is a book about families: mothers, grandmothers, fathers, grandfathers, and children, and how our families define us. The poems connect the poets to each other and to the world around them. As Laurie, Mary, Deborah, and Johanna conduct this poetic symphony, one voice emerges from their poetic meditations: a voice that calls for hope, and reminds us to pay attention to this world we share.

Love's Meditation

Laurie Hailey

26 December 2023: Soon after we opened in 2020 we had the pleasure to meet Jill Hedgecock and carry her books in our Local Authors bookcase, and we are very pleased to offer her congratulations on the third and final book in her Doberman-inspired Shadow the Doberman series, In Shadow's Reflection!

In Shadow's Reflection

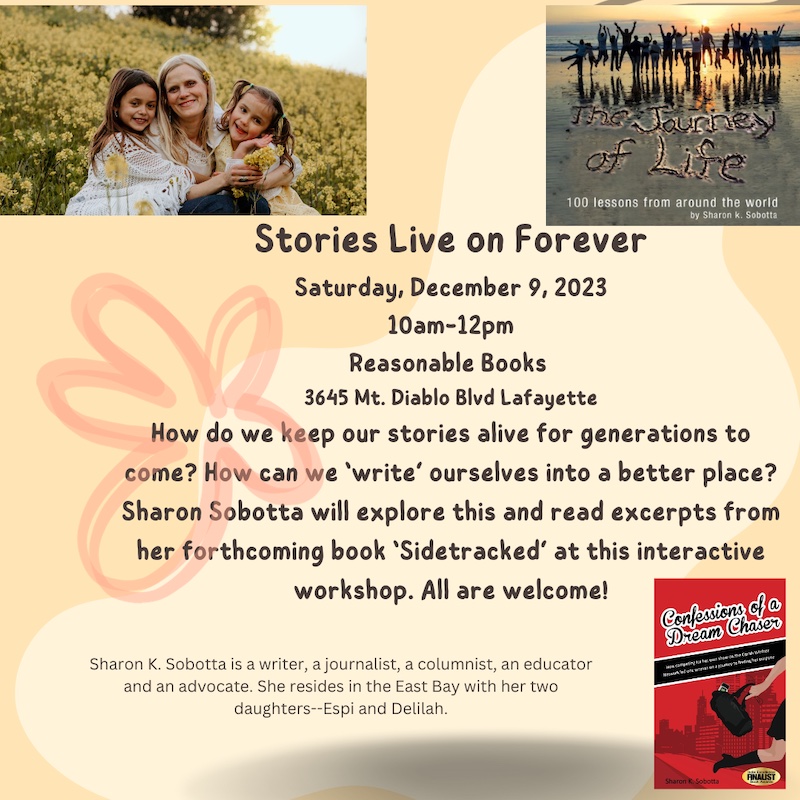

4 December 2023: Please RSVP for our next in-store event this Saturday, December 9th, at 10:00 AM, where we will host a writing workshop with Sharon Sobotta! You can email your RSVP to books@reasonable.online.

2024 2023 2022 2021 2020